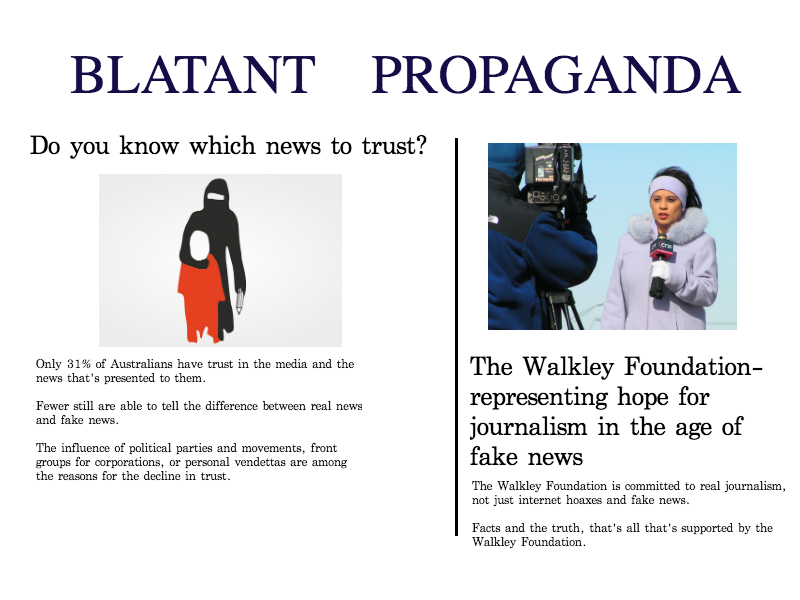

The Walkley Foundation is an organisation that supports ethical Australian journalism, and works to encourage a strong and innovative media environment. The concept pair I’ve decided to explore in my images is ‘real/manipulated’. I chose this pair because the idea of media manipulation is prevalent in the digital world, as fake news is widespread across digital spaces. My images aim to represent the Walkley Foundation as a strong supporter of ethical and truthful journalism, and as an antithesis to fake news.

I have chosen to use a collage approach to my images, placing the subject outside of their original context and giving new life to the image (Hall 2011).

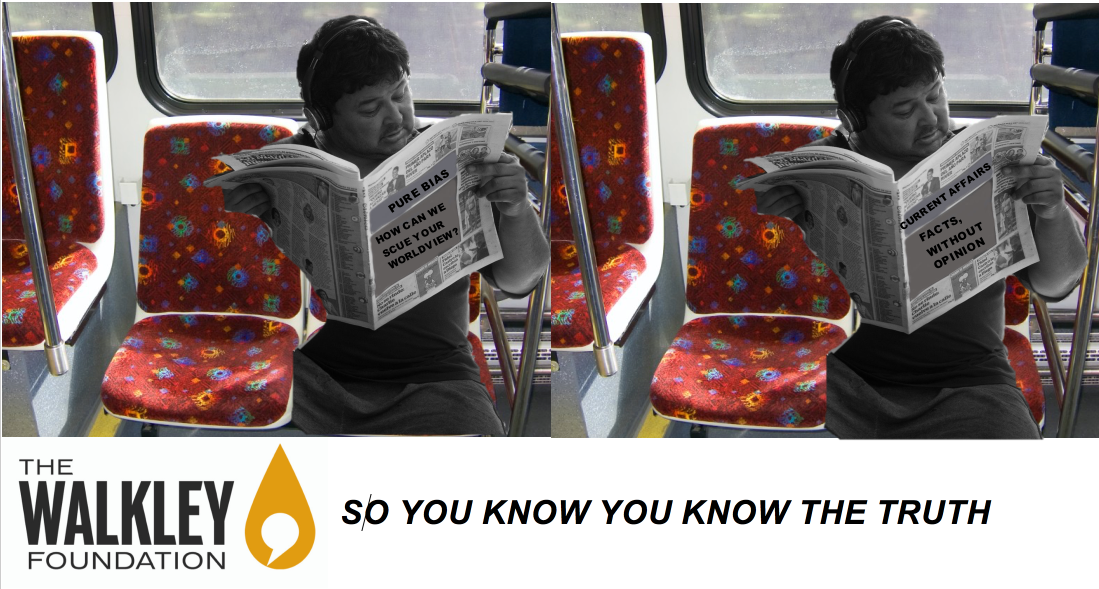

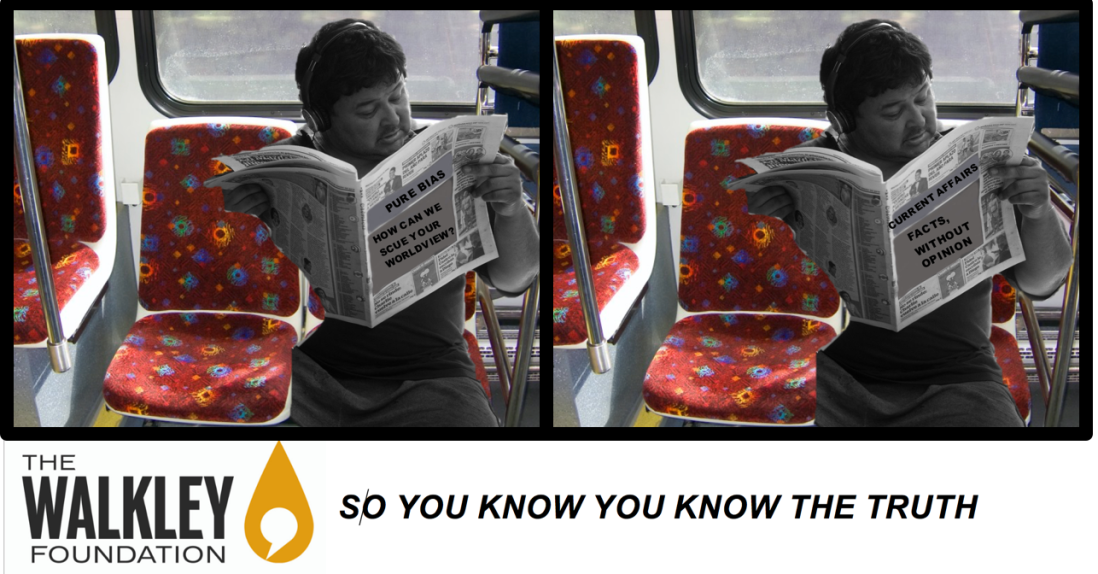

My first image centres around the idea of fake news in the political sphere. I’ve altered an image of a woman reading a newspaper to show two alternatives concerning news, one where the media produces fake news and one where the media produces trust worthy news. The rise of fake news following the 2016 election has created an extreme distrust in the media in the public (Mihailidis & Viotty 2017), and I wanted to showcase the Walkley Foundation as offering an alternative to that view of the media.

Utilising information value zones, I placed the altered image showing the ‘fake news’ newspaper on the left. Kress and van Leeuwen state that an effective use of splitting information includes placing “given” information on the left, and information on the “issue” you are exploring on the right (Kress & van Leeuwen 1996). The given understanding of the media in today’s climate is one of distrust, and the image on the left mirrors that. In placing the alternative view of the media on the right, I am allowing the viewer to consider the positive impact of the Walkley Foundation in the Australian media.

The use of symbolism is important for this image. I chose to use a print newspaper as opposed to a digital one as a tangible newspaper is a symbol of the ‘real’, whereas digital news has an association with being fake.

To create my altered newspaper, I used the pen tool to paint over the words on the page. I took great care to match the colour of the paper or section of paper, using the colour toggle on Pixlr to find the correct shade.

I wanted the image to have a closer association to the political sphere, so I used the ‘lasso’ tool to remove the woman from her original background and place her in the Oval Office of the US president, rather than in her original context. Fake news is closely linked to the US President following the 2016 Presidential Campaign (Mihailidis & Viotty 2017), something that I’ve mirrored in my image by placing the woman in the image in the Oval Office. This represents the link between political spheres and the media.